Next week, I’ll be talking about a project I’ve worked on for a decade now at the ARG-UK 2021 AGM. Obviously I won’t give too much away in this blog because spoilers are bad. However, I thought I’d talk a bit about the humble common frog, and summarise some of the work I’ve done on this species.

A long history of frogging

I love frogs, I always have. I am not even really all that sure why. However, ever since I was a kid catching frogs in a rank grassland at the corner of a football pitch, I’ve been hooked. Of course, now that I’m an adult I get to go catch frogs and call it science. Perfect!

I was fortunate in my childhood to grow up in a fairly rural community and so wildlife was reasonably abundant. I used to collect adult frogs, spawn, and tadpoles to raise in glass aquariums in our shed. It’s fair to say that I had quite an understanding mother.

Professional frog man

It was back in 2011 that I started formally recording frogs. One of the countryside rangers with South Lanarkshire Council set me down this path. He had given me a report from 2000 which censused the frog population of East Kilbride and surrounds. Together, we ground-truthed the records and took note of where the ponds were. I have to admit, I have since rather ran with it.

Next thing you knew, 20 year old Erik was here, there, and everywhere counting frog spawn clumps. I even had an article in the local newspaper asking for locals to let me come and look at their ponds. People actually got in touch too.

Frog science time

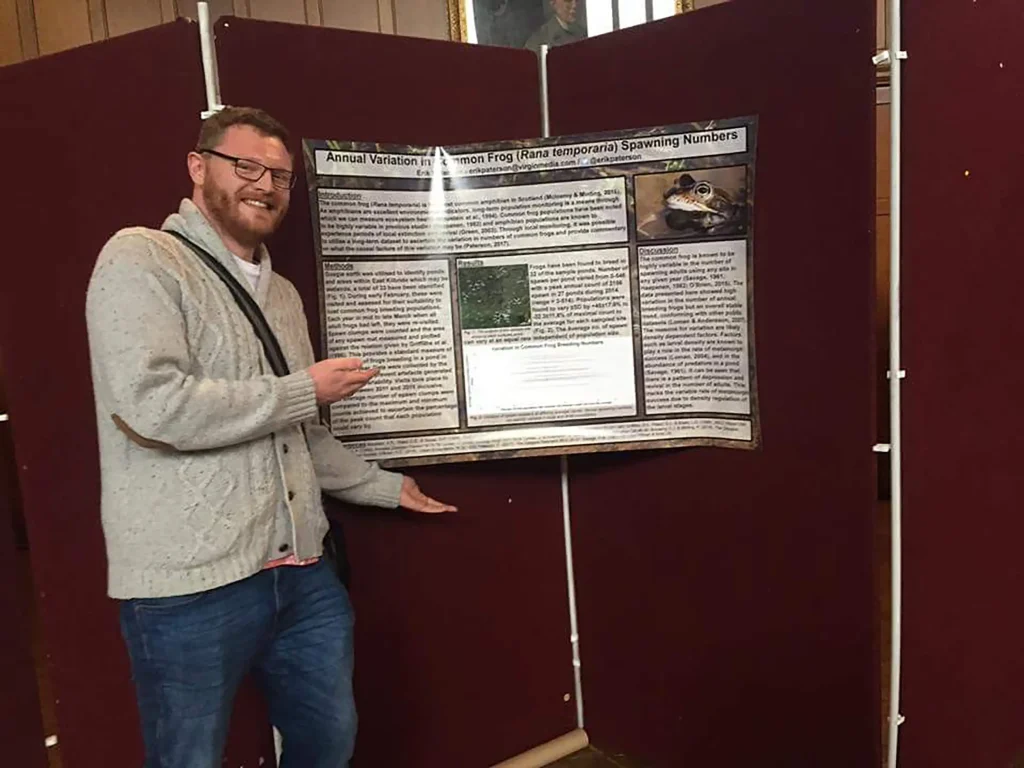

As I progressed through my early 20’s I began to feel mildly self conscious about the fact that I was counting frogs every year. So I decided that as I was obviously going to keep counting frogs, I should make it science. Thereafter I started looking at the data I had collected, and trying to work out if there was anything I could discern from it. There was indeed.

I noticed something I thought was odd about the between-year changes in the number of spawn clumps at any one site. These counts could be the same proportion of the maximum count ever at that pond from the average regardless of the size of the population. For example, a population with an average of 4 spawn clumps, and one with 400, could vary between years by as much as 35% of the total number of frogs breeding. I thought that was interesting and I was very pleased to have had a paper published in The Glasgow Naturalist talking about this.

Later on, I had a masters student from the University of Glasgow, Ryan Bird, join me on my project to look at the effects of pond pollution on developing frog larvae. His project looked at how this differed between SuDS systems designed to drain roads than it did from natural pond systems. We spoke at a conference about that and co-authored a paper which was also published in The Glasgow Naturalist with the results of his masters project.

Have a read of some of my other publications here.

Conservation in waiting

In the last few years, I’ve struggled to really be effective with my research. I was simply too busy and worn down in full time employment. With the relative freedoms afforded to me by self employment, I’m hoping to get out surveying more. My intentions are to try and use some of my volunteer time alongside the business to engage in some positive management of ponds. This should be to the benefit of the wildlife and to the people who enjoy them too.

A frog in my throat

Ah, yes, to the talk. So next week I will be presenting a general round-up of the amphibian survey efforts I have been completing in East Kilbride for the past decade. my talk will look at some of the data I’ve collected and examine what they might imply. I’ll also be looking at the unfortunate losses of ponds we’ve experienced in that time, and what that has meant for some of our less common species. Sign up to the AGM to listen.